Garbage collection is a type of automatic memory management that's used in many modern programming languages. The point of the garbage collector is to free up memory used by objects which are no longer being used by a program. Although it's convenient for developers not to think about manually deallocating memory, it can be a poisoned chalice that comes with several hard-to-predict downsides.

How can garbage collection cause performance issues?

Some garbage collectors completely halt the program's execution to make sure no new objects are created while it cleans up. To avoid these unpredictable stop-the-world pauses in a program, incremental and concurrent garbage collectors were developed. Although they provide great benefit in many cases, there's additional design choices that wind up back into development phases where you have to indirectly deal with memory allocation.

Another issue is that garbage collectors themselves consume resources to decide what to free up, which can add considerable overhead. Environments dealing with real-time data are latency-sensitive and require high performance and efficiency. In these applications, unpredictable halting behavior combined with excess computation time or memory usage is not acceptable.

As we're building an open source high-performance time series database, we have these environments in mind and use design patterns and tooling that focuses on writing code that's efficient and reliable. When we need additional functionality that would introduce performance knocks through standard libraries, we can leverage our own implementations using native methods. This is what prompted us to add a network stack that executes garbage-free.

This component bypasses Java's native non-blocking IO with our own notification system. This component's job is to delegate tasks to worker threads and use queues for events and TCP socket connections. The result is a new generic network stack used to handle all incoming network connections. Following our new support for Kafka, QuestDB's network stack now ingests time series data from Kafka topics reliably, without garbage collection.

TCP flow control

When we have multiple nodes on a network, there are usually disparities in their performance in computing power and network bandwidth. Some nodes can read incoming packets at different rates than others, or conversely, some nodes may be able to send data at a different rate.

Let's say we have a network with two nodes; a sender and a receiver. If the sender can produce a lot more data than the receiver can read, the receiver is likely to be overwhelmed. We're in luck, though, as TCP uses a built-in flow control protocol that acts as a pressure valve to ensure the receiver is not affected by such cases.

Control flow manifests itself in different ways, depending on whether the network socket is blocking or non-blocking. If the receiver can process data faster than a sender, a non-blocking socket is identical to a blocking one, and the receiver thread would be parked while no data is read. There's not much concern about this situation if it happens infrequently, but the park and unpark is a waste of resources and CPU cycles if the receiver is under heavy load.

Let's assume the receiver gets 0-length data on a non-blocking socket, indicating no data has arrived from the sender; there are two options:

- Loop over socket reads continuously, waiting for data to arrive.

- Stop looping and consult our parser on two possible actions to take: park for more reads or switch to write.

The first option is quite wasteful, so we went with the second approach. To park

socket read operations without blocking the thread, we need a dedicated system

for enqueuing and notifying us when the socket has more data to read. On the OS

kernel level, IO notification utilities exist as epoll on Linux, kqueue on

FreeBSD and OSX, and select on Windows. In QuestDB, we've implemented a

dispatcher that operates exactly as these IO notification systems for enqueuing

sockets, and we named it IODispatcher.

Java NIO and garbage collection

As you would expect from cross-platform languages, the IO Notification system

must be abstracted away to make application code portable. In Java, this

abstraction is called Selector. If we were to oversimplify a typical

interaction with the IO Notification system, it would essentially be a loop.

More often than not, this is an infinite loop, or rather, it executes

continuously during the server's uptime.

Since we are on a quest to have everything garbage-free, Selector presents a problem right away - the output of the selector is a set of keys, coming from a concurrent hash map via an iterator. All of this allocates objects on every iteration of the loop. If you are not careful, this allocation continues even when the server is idling. The behavior is intrinsic to the Java Non-blocking I/O (NIO) implementation and cannot be changed.

To send or receive data from the network, Java mandates ByteBuffer instances. When looked at in a vacuum, ByteBuffer may seem like a reasonable abstraction. But if we look closer, it's easy to see it's a bit confused. It is a concrete class instead of an interface, meaning that the whole NIO is stuck with the provided implementation. The API is inconsistent as the OS requires memory pointers for send and receive methods, but ByteBuffer does not provide an explicit semantic for each case. So how does ByteBuffer translate to a memory pointer?

When your data is on the heap, there is a memory copy for each socket IO. When ByteBuffer is direct, there is no copy, but there is an issue releasing memory and general Java paranoia about language safety.

/**

* /java.base/share/classes/sun/nio/ch/SocketChannelImpl.java

*/

public int write(ByteBuffer buf) throws IOException {

Objects.requireNonNull(buf);

writeLock.lock();

try {

boolean blocking = isBlocking();

int n = 0;

try {

beginWrite(blocking);

if (blocking) {

do {

n = IOUtil.write(fd, buf, -1, nd);

} while (n == IOStatus.INTERRUPTED && isOpen());

} else {

n = IOUtil.write(fd, buf, -1, nd);

}

} finally {

endWrite(blocking, n > 0);

if (n <= 0 && isOutputClosed)

throw new AsynchronousCloseException();

}

return IOStatus.normalize(n);

} finally {

writeLock.unlock();

}

}

Considering the allocating nature of the Selector, that Java NIO libraries are a layer above the OS, and how computationally expensive the overhead is with ByteBuffer, we decided to go out on a limb and interact directly with the OS via the Java Native Interface (JNI). This worked for QuestDB insofar as the API is non-allocating outside of the normal bootstrap phase and lets us work with the memory pointers directly.

/**

* /core/src/main/c/share/net.c

*/

JNIEXPORT jint JNICALL Java_io_questdb_network_Net_send

(JNIEnv *e, jclass cl, jlong fd, jlong ptr, jint len) {

const ssize_t n = send((int) fd, (const void *) ptr, (size_t) len, 0);

if (n > -1) {

return n;

}

if (errno == EWOULDBLOCK) {

return com_questdb_network_Net_ERETRY;

}

return com_questdb_network_Net_EOTHERDISCONNECT;

}

QuestDB's thread model

Starting threads is expensive, and they're more often than not just wrappers for the connection state. QuestDB operates a fixed number of threads to isolate the database instance to specific cores and reduce the overhead of starting and stopping threads at runtime. The actual threads are encapsulated by a WorkerPool class.

The worker pool's idea is to have a simple list of "jobs" that all workers will run all the time. Jobs themselves encapsulate "piece of work" and do not have tight loops in them. Hence a job can simply return if IO is not available or the queue is full or empty.

We have a notion of a "synchronized job." It is different from the definition of "synchronized" in Java in that the QuestDB's thread never blocks. However, synchronized jobs guarantee that only one thread can execute a job instance at any moment in time.

Adding an IO notification loop

IODispatcher is QuestDB's implementation of the IO Notification loop. We have

implemented epoll, kqueue, and select, so this works cross-platform. The

appropriate implementation is automatically chosen at runtime based on the OS.

The IODispatched API is message-driven via QuestDB's implementation of

non-blocking and non-allocating queues. These queues are outside of the scope of

this article, but you can read about them in our community

contribution from Alex Pelagenko.

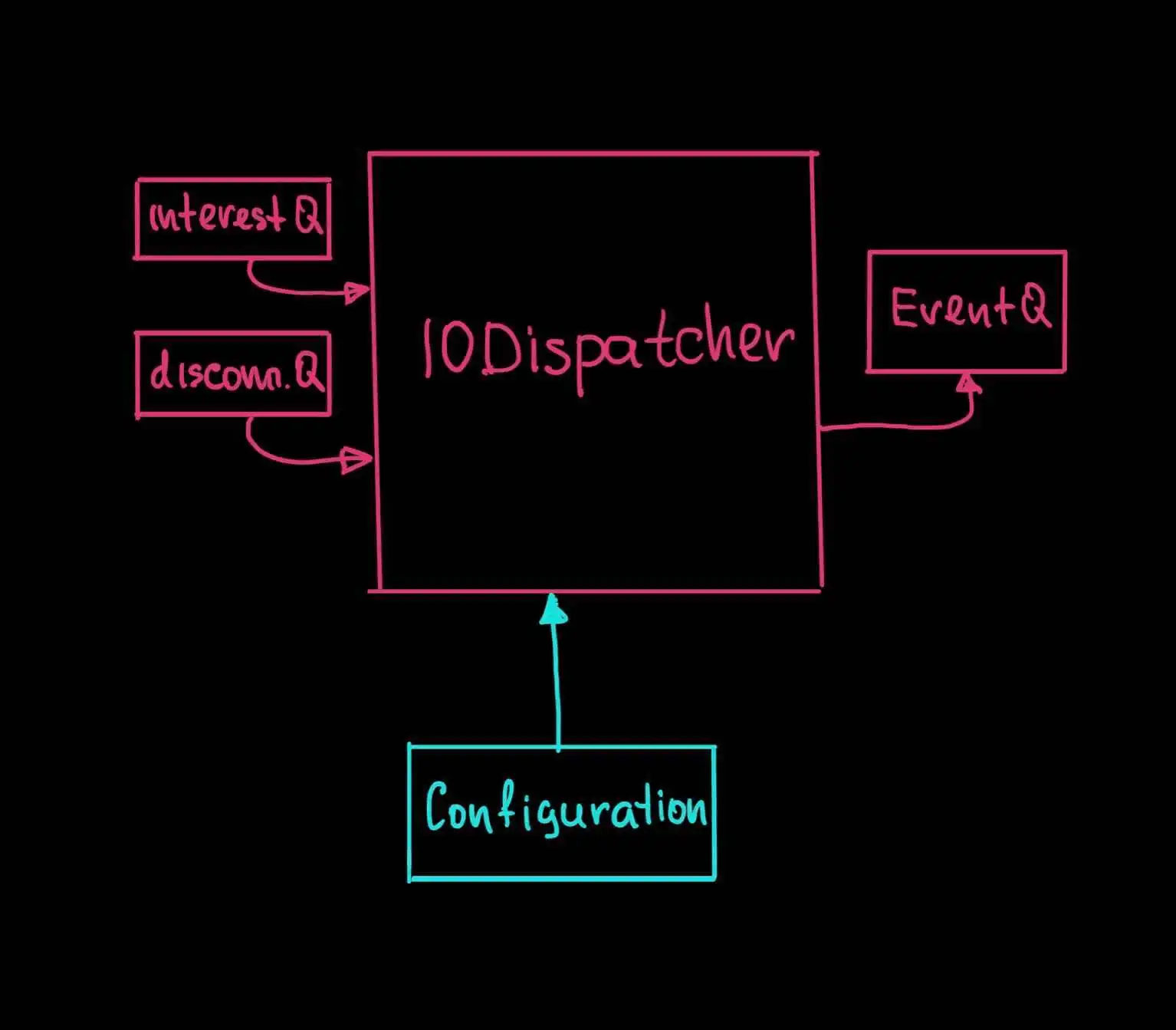

IODispatcher is a synchronized job in context of QuestDB's thread model. It consumes queues on the left and publishes to the queue on the right. IODispatcher's main responsibility is to deliver socket handles (individual connection identifiers), that are ready for the IO to the worker threads. Considering that socket handles are read or written to by one thread at a time the underlying IO notification system works in ONESHOT mode. This means socket handle is removed from the IO notification system while there is socket activity and re-introduced back when activity tapers off. Interacting with the IO notification system is expensive. Worker thread will only recurse back to the IODispatcher for enqueueing if there has been zero data from the socket for the set period of time, which we call hysteresis.

You can find source code of the implementations of the IODispatcher for epoll , kqueue and select on GitHub. Let's take a look at the components in the diagram above with an outline of their purpose:

IO Event Queue: Single publisher, multiple consumer queue. It is the recipient of the IO events from as in epoll, kqueue, select. The events are socket handles and the type of operation the OS has associated them with, e.g., read or write. The IODispatcher plays the publisher role, and any number of worker threads are the consumers.

Interest Queue: Multiple publisher, single consumer queue. Worker threads publish socket handles and operations to this queue when IO is unavailable, e.g., socket read or write returns zero. The IODispatcher will enqueue the socket handle for more reads or writes as defined by the operation.

Disconnect Queue: Multiple publisher, single consumer queue. Worker threads publish socket handles to this queue destined to be disconnected from the server and have their resources reused by other connections. The worker thread does not disconnect the socket by itself because multiple threads may attempt to access a data structure that is not thread-safe.

Configuring network IO�

We disregarded ByteBuffer for not being an interface, so it would only be fair for us to have interfaces in key places. One of these places is configuration, which provides IODispatcher with basics such as:

- The IP address of the network interface

- Port to bind to

- Bias

- Buffer sizes

- Network facade

- Clock facade

- Connection context factory

It's necessary to explain bias here, which might not be so obvious. When the TCP connection is first accepted, it is enqueued for IO right away. The bias provides an expectation of the initial operation of a connection, such as read or write. For example, most TCP protocols would have 'read bias', which means that connecting clients will have to send data before the server replies anything. You can probably think of a protocol that requires the server to respond first before the client sends anything - in this case, the bias will be 'write'.

Network & clock facades have static implementations for production runtime, but for tests, they can be both spot-implemented to simulate OS failures and produce stable timestamps.

Connection Context

Connection context is a Java object that encapsulates the connection state, which is protocol-specific. It is stored together with the socket handle and managed by IODispatcher via the context factory. We talked a little about the QuestDB thread model and that workers are very likely to execute the same job instance simultaneously unless the job is synchronized. In this scenario, the only place a job can reliably store a state is the connection context.

Protocol Parsers

Protocol parsers are used by worker threads to make sense of the incoming data. QuestDB has a convention that all protocol parsers must be streaming, e.g., they never hold on to the entirety of the data sent over the network. These parsers are typically state machines, with state held in connection context. This type of parser allows fully real-time ingestion of large data segments, such as text file import.

Worker Threads

Worker threads are required to consume the IO event queue. We already mentioned that the IODispatcher neither reads nor writes connected sockets itself. This is the responsibility of the worker threads.

Worker threads almost always use protocol parsers to interpret socket data. They must continue to work with the socket until the socket cannot read or write anymore. In which case, the worker threads either express "interest" in further socket interaction or disconnects the socket. In this situation, IODispatcher is not on the execution path during most of the socket interaction.

Threads will often use hysteresis, which means that they busy-spin socket read or write operations until either the socket responds or the number of iterations has elapsed. This is sometimes useful when a remote socket is able to respond with minimum delay.

Take a look

In this article, we've covered our approach to implementing non-blocking IO using what we think is a nice solution that's garbage-free. Kafka Connect support is now available since version 5.0.5. Our new network stack ingests time series data from Kafka topics reliably from multiple TCP connections on a single thread without garbage collection and the QuestDB source is open to browse on GitHub. If you like this content and our approach to non-blocking and garbage-free IO, or if you know of a better way to approach what we built, we'd love to know your thoughts! Feel free to share your feedback join our community forums.